There is an undeniable and absolutely visceral thrill in visiting a famous work of architecture for the first time. At least there is for me. I'm talking butterflies in the stomach, fanboy type stuff. You turn a city corner or drive down a lane or walk thorough a garden and it's there. That work. Those walls. Those spaces. Those materials. That thing you have looked at in books or magazines or guides and suddenly it's right there in front of you for you to take in. To touch. To feel in your soul. It never gets old. No matter how much or how often or how infrequently I do it. It's exhilarating.

I've experienced this feeling a lot in my life. I made a promise to myself when I graduated architecture school in early 1994 that I would spend my vacations at least once a year doing this. Seeking out the works of architecture I'd admired most in school and taking everything in. Paris. Finland. Amsterdam. Brussels. All over the United States. Each time, a thrill. A discovery. A confirmation that what I felt looking at pictures in a book was even better in person. Or most times anyway; sometimes (and not often) they disappointed me. But then again sometimes they made me drop to my knees in awe, which is probably a little melodramatic, but it did actually happen once.

I kept this stuff up for a while. I was pretty diligent and committed from 1994 to about 2007. I read guidebooks. I made maps. I lugged a camera all over the place that was way heavier than I would even think about carrying now. I filled eight 3" binders with slides that I rarely look at even though I DO still own a slide projector. Then I ran out of stuff to see. Or got interested in something else. Or maybe a little bit of both. OK, maybe more the latter.

In the years since 2007, I've traveled way wider and further than I ever had before. And in between safaris and walks to ancient Incan citadels and birdwatching and everything else I've been up to, I've managed to pick up some buildings that I missed between '94 and '07. The Maison de Verre in Paris. All of Antoni Gaudí's work in Barcelona. The Pantheon in Rome. Maybe some others.

Talk about a weak knees moment, by the way. My heart about stopped with joy when I found the Pantheon.

There were still some others out there on a mental list, including a probably pretty impractical house designed by Mies van der Rohe for Dr. Edith Farnsworth in Plano, Illinois, just about 60 miles or so west of Chicago.

I've had the Farnsworth House on my list for years. I've also visited Chicago at least four times since I started traveling in a serious way twenty seven years ago. I never went there. It seemed too far. But with the world seemingly off limits for travel for most of this year, this seemed like the ideal time to pick off some of my longstanding domestic sites that I'd just never gotten around to visiting. 2021 had to be the year I made it to the Farnsworth House. There was really no good excuse for passing this up for another year. And now...mission accomplished!

I made my way to the Farnsworth House with some pretty strong preconceived notions and none of them were flattering to either the house or the architect. The story of the house likely started as a chance meeting between Dr. Farnsworth and Mies at a party of some sort in the mid-1940s. Dr. Farnsworth was tired of staying in the city on weekends in the summers and longed for a country house where she could escape Chicago for a few days every week. Mies had the answer, one that turned out to be a glass box with precious few walls along the banks of a river prone to flooding. I told you there was bias.

Who does this? Who goes along with such a seemingly preposterous idea? And one that, by the way, ended up costing about 75% more than the desired price. A glass house for a single woman in rural Illinois. Are you kidding me? What is wrong with these clients who agree to these ideas kicked around by the famous architects they hire. I get it a little bit. Maybe I don't have enough money to get it completely.

I'll also say this: I'm an architect and I don't get why Mies van der Rohe is so revered. He often pops up on lists of the very best architects of the 20th century (usually alongside Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier) and I don't understand it at all. I see no warmth. I see spaces that don't move me. I see skyscrapers with structural columns glued onto the exterior of buildings in a non-structural way and I don't get it. I don't want to touch Mies' buildings, and architects are famous (or infamous) for touching buildings; it makes us feel good somehow.

But since I'd never been in one of his residences, I thought I should give it a shot.

The approach to the Farnsworth House, the thing that builds that anticipation of that first view, is pretty much perfect. From the visitor center (obviously not in place during the time Edith Farnsworth owned the place), it is a gentle, half mile walk along, but separated from, the Fox River. The trees conceal the house until you reach the front patio and the place is revealed. I can't give Mies credit for this. Or Edith Farnsworth. Because the walkway was installed by Lord Peter Palumbo, who bought the house from Farnsworth. But it is pretty much perfect. A complete "oh my God, there it is (finally!)" moment.

Or it would be, if the fence surrounding the patio under reconstruction weren't there like it was when we visited. You can still get the sense that this reveal is correct. It would have been spectacular without that construction fencing. And one day, the fencing will go away again.

Two things on that first impression. First, the house seemed heavier than I thought it would. It didn't seem like a glass house. This is an impression that I would continue to have while walking through the house. The intent of the removal of the barrier between outside and in didn't seem to me like it worked. From either the outside or in. I felt inside when I was inside the house and I didn't feel space flowing into the house when I was on the exterior. I felt that the house was a heavy object when I was outside. It's the thickness of the floor and roof slabs, I think.

Second, it seemed way higher off the ground than I thought it would be. I expected a couple of feet. We were told 5'-3". If there's a rub with me and this house, it's the whole flooding thing. The house is notorious for being underwater when it shouldn't be (which is never). I expected the reason the place would be consumed by the Fox River so much was that it was so close to the water and it was so close to the ground. Mies apparently tried pretty hard to get the floor of the house high enough to avoid flooding. The problem was he really relied on rumor and folklore as his science when determining the first floor elevation.

|

| The Farnsworth House awaits!!! |

|

| The patio under construction. |

The story behind the siting of the Farnsworth House is that Mies really wanted it next a venerable maple tree near the river's edge. The tree would provide shade for the house in summer and protect it from getting too hot. He was advised to site the house further inland on the top of the slope to the street side of the property, but the allure of that maple was too much.

I guess he tried to get it right. He asked around with some local dudes about their memory of how high the river would get. They gave Mies their input: three feet was the answer. Mies erred on the side of caution and made it 5'-3". He missed the mark by about five feet. Yes, the river flooded its banks by about 10 feet one year.

That's FIVE FEET above the floor of the house!!! How do you mess it up that badly? I mean I know the answer to that is in the previous paragraph (he asked the neighbors) but how is checking with some locals the way to get to an answer this critical? The Farnsworth House (to me) is as famous for flooding as it is famous for its design. Major fail!

The irony is that the tree that located the building is gone. Oh well...

|

| The front of the house and the stump of the maple. |

Flooding and heaviness. That's what I got. I know my cynicism is showing through right now.Then I went inside.

First off, let me say that the tour of this house is awesome. You get incredible information. You get a ton of time. And you get to take as many pictures as you want with so few people on the tour that you can really get all the pics you want without any issue. I'm not sure I can say this quite about any other famous house I've visited. I appreciate the access. No shoes and no touching but that's understandable really. This tour is special.

I am astonished to be writing these next words but the interior of this house was one of the best places I have been in years. The flow, the openness, the views, the light. All of that was so impressive. I continue to maintain that the separation between out and in was clearly there (there was no way we were outside when we were inside the Farnsworth House). I saw the glass and the floor elevation as separators from the landscape beyond. It didn't matter. I'm so in love that I would consider buying one of these (without the flooding, of course, and the leaks and the condensation) to hang out in on weekends. If this is supposed to be a weekend house, I buy it. I totally get it.

I can't afford one of these, for the record.

Admittedly, there are some quirks and some mistakes and a little vanity to the place. The porch echoes. It's noticeable when a tour guide is talking to you in there (although he supposed it might be advantageous to Edith Farnsworth's violin playing). The fireplace lacked a hearth originally; the wood just sat on the floor and the ash tended to blow around the place when the door and the two windows in the place were open at the same time (Palumbo fixed that one just like he did the approach to the house). And the kitchen has a custom light fixture designed specifically to show off the world's largest (at the time) stainless steel counter to people on the outside of the house looking in. I mean, why do you need this? why do you need to show off the kitchen counter at night to people looking at the house?

But the scale in the place is right. It seems way smaller on the inside than it does from the outside and this is a good thing. The furniture fits in the place. There's enough space to sit, to read, to relax and to entertain. This seems like a weekend house. Just ignore the flooding.

|

| The kitchen. Check out that countertop. |

|

| And the light fixture. To show off the countertop. |

It's right...except for the bedroom. I was honestly OK with the whole thing except for the bedroom. It's a weekend house. You have to sleep there. I'm not sure that Mies was really totally accepting of that concept.

Bedrooms are inherently private. Glass houses are inherently not private. That stainless steel counter lit up to show it off from the outside of the house? About four feet from the location of the bed. And there's no door between the kitchen and bedroom. Or maybe bed area is a better term.

The design of the bed area was a bit of a bone of contention between Mies and Edith Farnsworth, apparently. Mies had this vision of no walls but eventually caved and agreed on a wardrobe that would stop well short of the ceiling to (in a sort of a limited way) cordon off the bed area from the rest of the house. They argued about the height of that wardrobe (Mies insisted on five feet which was not as tall as Dr. Farnsworth) before she worked around him and agreed to the wardrobe but got one of his associates to design it taller.

I really can't imagine sleeping in the bed area comfortably, and that's coming from a grown man in 2021. I know it was originally a nine acre estate that was later expanded to triple that size and I also know there was not supposed to be anyone outside looking in (despite the whole kitchen light fixture thing), but there is so little keeping that area private. Maybe it's just me.

|

| Private? Not exactly. The bathroom was way bigger than I expected. |

So...overall despite the flooding and the privacy in the bedroom thing, I'm thumbs up on this one. I know..it's crazy. I'm crazy! But I can completely understand why Mies thinks he got this one right. The place is really pretty stunning. I'm actually very impressed. And that was on a visit with the terrace under construction. Not only did that issue affect the entry sequence, it also added the wooden stair shown in the second picture of this post which is decidedly NOT part of the permanent house. I'm on board. I'm shocked.

Now, I wouldn't be an architect if I didn't say a little something about some of the details. So here goes.

One of the more celebrated details of the house is the connection between the vertical columns and the horizontal floor and roof planes. This connection is a welded steel to steel connection and welded connections show. Which of course Mies didn't want. He wanted the column and beam / floor to appear to be magically glued together, so he made the workers grind the welds down until the connection was pretty much invisible. He got his way. It looks the way he wanted.

Detail #2: If we were disappointed by the ongoing reconstruction of the terrace (and we were), at least we got to check out the thickness (or thinness) of the travertine marble slabs laid on the terrace (and throughout the whole house for that matter). They are remarkably thin. We found them stacked on the tennis court. The 70 year old travertine looked way better than the tennis court did.

Finally, there is no picture that I have ever seen of the Farnsworth House that shows how sewage leaves the place. I mean it's more than five feet off the surface of the Earth, right? But sure enough, there's a concrete cylinder below the house that contains all the services in to and out of the house. It has to be there; it's just never shown in pictures, that's all.

|

| Welded connection. Or is it? |

|

| Travertine. It's thin, right? I think it is. |

Despite my generally positive review of the place (admittedly some of it due to the almost unrestricted access to the property on our tour), the coming together of the Farnsworth House was not a painless process. Design started in 1946 with a promised $40,000 budget (that's about 1/10 of 2021 dollars) and the house wasn't ready for occupation until the absolute last day of 1950 (how cold was that first night?). And with a $70,000 price tag.

Mies eventually sued Edith Farnsworth and she eventually sued him back. She lost. Or more accurately, she ended up having to pay him $1,500. But they probably both really lost. There is an introductory video played at the beginning of the Farnsworth House tour. During that video there is a quote attributed to Dr. Farnsworth that goes "My house is a monument to Mies van der Rohe. And I'm paying for it."

She's probably mostly right. There are not a lot of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe houses out there (the Tugendhat House in Czechia sticks out as another one but I can't say I can think of any others). He's different from some of his contemporaries in that regard. This one got some things very wrong, but it also got some things really right. And sure, she paid for it, but it's also in some ways a monument to her, not that she likely wanted that. But it took both of them to make this house.

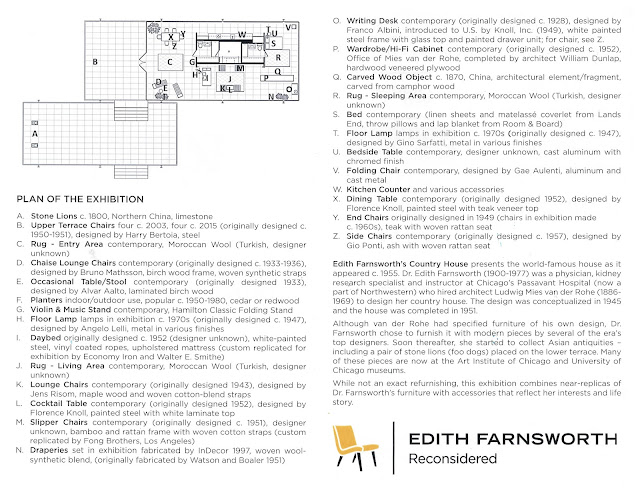

The National Trust for Historic Preservation (which owns the house today) decided that they would (at least for 2021) stage the house as Edith Farnsworth, and not Mies, wanted it. Like most architects, Mies was a control freak, and tended not to tolerate anything about his buildings that was not the way he intended, including the objects and furniture placed within.

I tend to disagree with the master here and go with the client. We should have furniture in our houses that makes us feel comfortable, not that which looks best in the eyes of the architect. We should also be able to hang whatever we want on the walls. After all, we paid for it. I love the objects in Edith Farnsworth's weekend house. For posterity and as a close to this post, I'm including below the key to the objects on display when we were there. This is some pretty good stuff. Both Mies and Edith Farnsworth should be proud of what they did here. It's too bad that the process was so difficult.

How We Did It

The Farnsworth House is located in Plano, Illinois about a 55 mile drive west and a bit south from Chicago. The National Trust for Historic Preservation operates a series of different tours, (including in depth, grounds-only, seasonal and nighttime tours) Wednesday through Sunday at various times. Check their website for all the options. We took the "Guided Tour of the EFCH" and it was thoroughly awesome. Photographs are allowed. Or at least they are with an iPhone. I'd suggest a reservation in advance because I always have reservations. It just prevents the off chance of huge disappointment.

Earlier this year, I read Alex Beam's book, Broken Glass, which is an account of the relationship between Dr. Farnsworth and Mies and the story of the design and construction of the house and the ensuing lawsuits. I read it right after the new year and it made me determined to visit. It worked!

Finally, there's a field of soybeans right next to the visitor center parking lot. From afar, they looked like a field of flowers somewhere in some European country. I thought they looked awesome, so I took a pic and made it the cover of this blog post.